My research explores art and religion in the ancient Greek world, with a focus on Southern Italy. I combine art history, archaeology, and literature to explore how ritual negotiates relations between humans and a supra-natural world.

My work is object-focused — foregrounding archaeologically and historically contextualized experiences of the material world. My main scholarly interest is the art of ancient Greece, broadly conceived of as archaic, classical, and Hellenistic Greece with a particular focus on colonial Southern Italy, and the Greek’s cultural interlocutors throughout the Mediterranean. I’m also interested in the reception of these Greek images and ideas in pre-Roman Italy, throughout the Roman period, early modern Europe, and into modern and contemporary popular culture. Votive objects, grave goods, apotropaic images, and images of the divine are particularly useful for thinking through my research questions, as they facilitate relationships between the human and a more-than-human that encompasses gods and goats, stones and statues. The goal of my research, broadly speaking, is to develop a multi-temporal, kaleidoscopic perspective on a rapturously material Greek world.

Forthcoming Academic Publications:

“The Satyr, the Krater, and Hegel: Mediated Subjectivity in a Peucetian Burial,” in Bennet, Hedreen, Kim, and Laferrière (eds.) Phenomenology & the Painted Vase. (Forthcoming 2025, U of Wisconsin Press).

“Burial and the Ritual Body: Pantanello, Tomb 126,” in Kim and Mazurek (eds.) Ritualizing Bodies. (Forthcoming 2026, Cambridge University Press).

Upcoming Talks:

“Picturing Funerary Rites in Turn-of-the-Fourth Century BCE South Italian Vase Painting.” Image et ritual dans l’Italie et la Sicile antiques (IRIS). Paris. 10 Oct. 2025.

Here are some of the areas I’ve been working in, and where I’m looking to go with them next:

Dissertation Project: Land and the Art of Burial in Colonial Southern Italy

My dissertation explores the construction of place-based ancestry at the turn of the fourth-century BCE, taking the colonial cities of Metaponto and Taranto as entry points into the culturally mixed Greek and Italic regions of Apulia and Lucania. In contrast to traditional perspectives of colonial land as possession, I argue that the material presence of the dead within the landscape both required and provided the means by which relationships with place could be constructed. A city founder’s scattered ashes could quite literally decolonize a polis, reclaiming the site for a displaced population. A partially buried amphora could become a conduit between those on the earth’s surface and those in its interior. And images of grave monuments on locally produced South Italian vases were not mere derivations of Attic imagery, but remarkably self-reflexive, mobile explorations of where and how the dead remain present, filtering Attic conventions through both Greek and local Italic funerary practices.

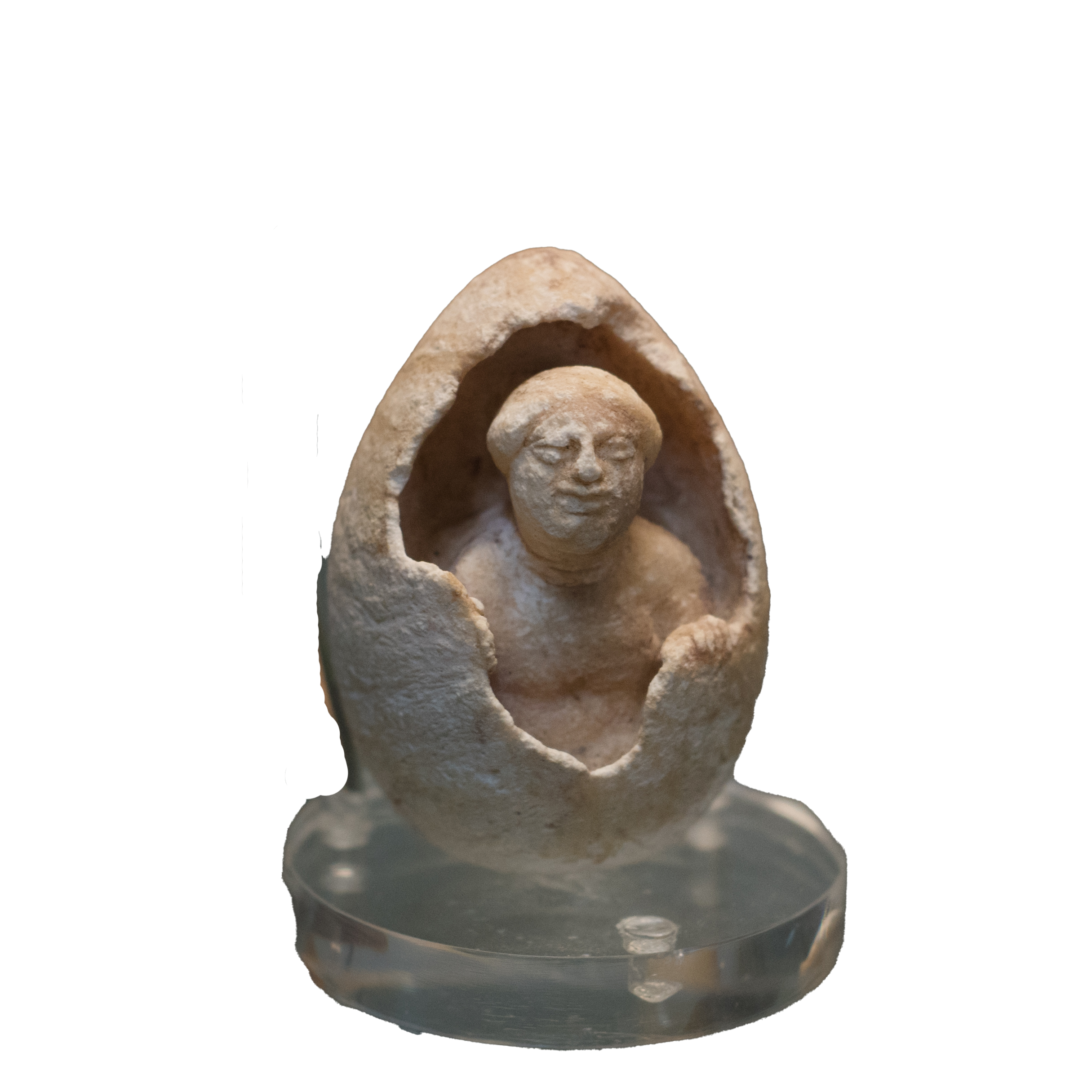

Votive Offerings and Grave Goods

A structuralist understanding of the Greek cosmos divides the world into three categories: animals, humans, and gods. Much of Greek religious ritual navigates relationships between these categories. Votive offerings, in the form of beautifully painted pots, masks, statues of young men and women, and scenes of sacrifice stand as material witnesses to these processes. I’m looking to further explore how objects and images, hypothetically “inert” matter, create or challenge divisions between mortals and immortals.

Like votives, grave goods also negotiated relationships between the human and the more-than-human world. Much of the recent scholarship on votives has viewed these objects as theological tools, centering their religious function. Yet grave goods, particularly those interred in Italian tombs, are far more often mined for the information about craft, cultural exchange, and trade. What would it mean to reintroduce the religious, ritual, and theological dimensions to the tomb?

Posthumanism and Critical Animal Studies

How can we talk about “posthumanism” in the premodern The art and literature of ancient Greece—in which a god can become a swan and produces mortal offspring with a human woman, an immortal horse weeps and speaks, and a statue of a god can be the deity—proves fertile ground for such an investigation. I am particularly interested in applying posthumanism attention of how matter and other than human beings can act to Greek religion and philosophy. Right now I’m fascinated by how materialist philosophies of the presocratics, particularly Empedocles, articulate the relationship between human and other-than-human beings.

Critical Historiography and Classical Reception

The art of Greco-Roman antiquity is often termed “classical,” but what exactly does that mean? The idea of a pure, white, “classical” ancient Mediterranean has long provided the foundation for white supremacist, patriarchal conceptions of “civilization,” and my work on critical classical reception attempts to directly address this legacy. I’m interested both in how the “classical tradition” is constructed, and how scholars and the general public can engage with it critically and more productively.